After a few years of sea kayaking and having owned nothing less than 13 sea kayaks and personally worked on 10 belonging to other people I have seen a few weaknesses in design and manufacture.

The list that follows is my personal experience of actual fails that I have observed up close. Fortunately not all on my kayaks

J

1) The most common failure I had on my composite sea kayaks (I have never owned a plastic one) is cracking of the laminate.

Occasionally the hull of my kayak hit a rock and produced damages of various degrees: on one occasion holing a thin laminated hull with surprisingly very little impact force.

Some other cracks in the hull have occurred from stressing the boat in heavy seas. The cockpit area is particularly prone to stress since there is no deck to create a solid monocoque structure.

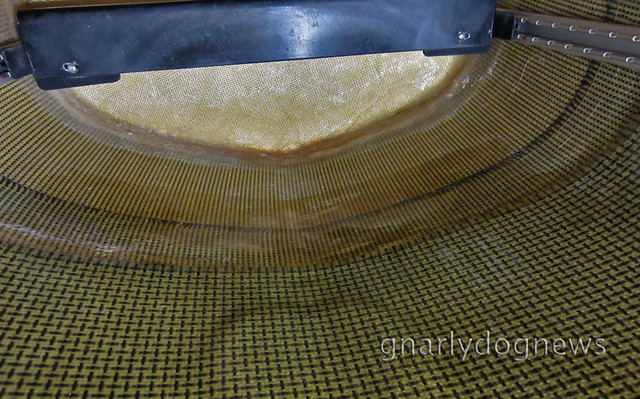

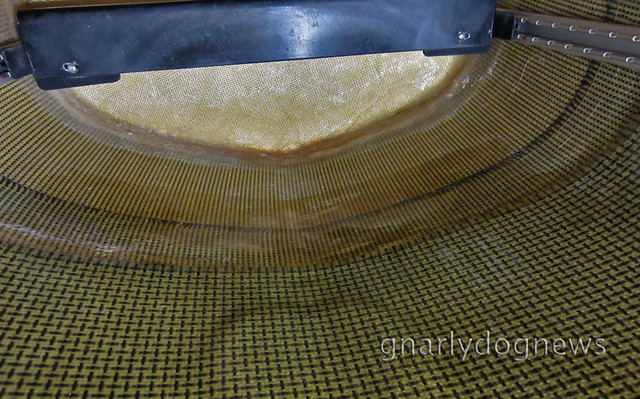

The hull under the seat is at its widest and flattest area: compression and flexing of the hull is common even on high-end kayaks. I have reinforced all of my current kayaks (apart from the hard chined Zegul) with a layer of carbon/Kevlar or double bias carbon to strengthen and stiffen a weak cockpit.

additional layers of carbon/Kevlar in cockpit area

additional layers of carbon/Kevlar in cockpit area

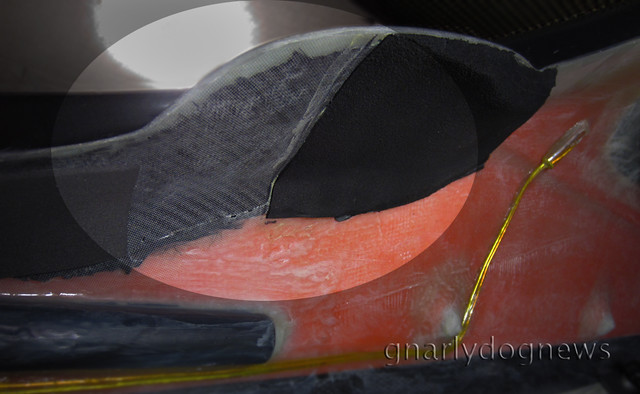

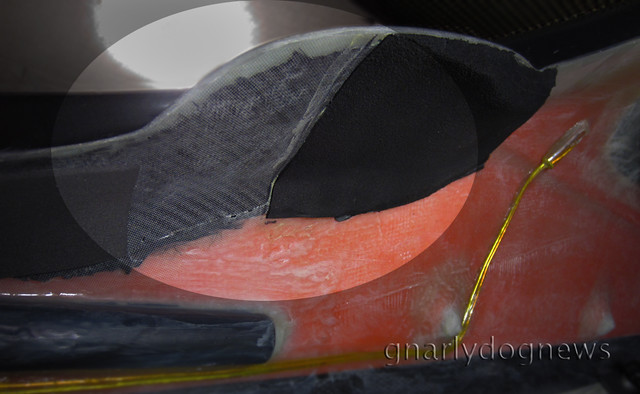

2) The cockpit coaming/deck joint has so far cracked in all my latest kayaks unless reinforced. These days I put a new boat on the “blocks” before it even hits the water. I remove any foam padding in the thigh braces and laminate the area with carbon.

In the boats I have not done so I have eventually stressed the deck enough to create hairline cracks in the deck. When rolling and edging in the surf, the kayak sees a lot of upward pressure from bracing with my thighs. Manufacturers rarely address/reinforce the coaming.

layers of carbon reinforcing the coaming/deck junction in thigh brace area

layers of carbon reinforcing the coaming/deck junction in thigh brace area

3) Speaking of junctions, the other common failure is the seam of the hull/deck. So far none of my kayaks have suffered a leak there but I have seen numerous kayaks without external seams develop a hairline crack that inevitably results in water entering the hatches. Adding a cosmetically acceptable external seam to a friend’s cracking kayak has been very time consuming. I only use epoxy for my work and I finished the seam with a coat of UV resistant black resin. A flow coat would have been easier tho…

4) And while I talk about cracks I should mention that most kayak manufacturers skip on the design and strength of the deck. The inexperienced might be fooled by a thick lay-up but rarely does he/she realize that glass-poor chopped strand (chopper gun lay-up) is suitable for very tick laminates like in a motorboat but are very poor executions for a sea kayak. Problems start to occur when a person needs to climb on the deck of a kayak in a recovery. So far I have repaired and reinforced half a dozen decks that failed under the weight of paddlers. On the other hand, my very light Chinese kayak has a core laminated deck making it extremely resilient. Other kayaks I now own have fabric instead of just chopped stand in the deck lay-up, and so far have held up very well.

underdeck hatch cover coaming area reinforced with carbon cloth

underdeck hatch cover coaming area reinforced with carbon cloth

5) Leaks to the hatches are often lamented by sea kayakers that paddle in conditions that will see water wash over the deck or proficient rollers that submerge the hatch covers.

I have had a few hatches leak. The most common problem has been water ingress from fittings on the deck.

deck fitting "well" where water pools

deck fitting "well" where water pools

The little well where the hardware is bolted to the fiberglass holds water that slowly seeps through to the inside if there is no proper sealing under the nut against the deck. Kayaks that have

recessed deck anchors don’t have that problem.

I had leaks coming from the junction of the hatch’s rim where the bonding sealant was not completely encompassing the rim. All it takes is a small section left out and water will seep in.

I have removed poorly fitted hatch rims and resealed them with polyurethane or epoxy glue.

6) Hatch covers are also prone to leak. So far only Valley and Kajak-Sport hatches have proven to be leak proof in my fleet. All other have leaked, even if often just minimally. Mind you, the Valley hatch covers have a reputation of deteriorating sometimes prematurely. Replacement of those is not cheap. Luckily there seems to be improvements on the quality of the Valley hatches and there are less reports for the need to replace them too soon.

Excellent alternative/replacement hatch covers are available from SEA-LECT Designs.

7) While most leaks occur from the top of the deck I have repaired 3 kayaks with leaking bulkheads. On one occasion the seal around the fiberglass bulkhead was not that great: a small amount of epoxy glue fixed the little hole. In two other instances I had to fabricate new bulkheads since the factory ones were made out of closed cell foam. It is just a matter of time before a foam bulkhead will leak. If a kayak is used in waves the hull/deck will flex enough to separate the weak glue that bonds foam to fiberglass (things get really ugly in plastic kayaks). Lifting the kayak by the rear of the cockpit coaming will separate the foam too. To date I have not met anybody with dry hatches in a kayak with foam bulkheads. I would only choose a plastic kayak that has

welded plastic bulkheads.

8) Small leaks to the cockpit area usually go unnoticed since water entering through the tunnel of the spray deck is greater than around the coaming junction. There have been however a few cases (not mine) where the rim was so poorly bonded that a low-deck kayak was flooding every half an hour. A large section was left out and not bonded at the factory. I have also observed a brand new, very high-end British kayaks, that had a visibly separating rim. It pays to inspect the new kayak before purchase.

coaming separating from deck

coaming separating from deck

9)

Last but not least leaks can occur from skeg cable housings or rudder lines. I had a badly glassed-in skeg box that leaked substantially. Gel coat concealed the cavity and only a small crack was visible inside the recess. Epoxy glue fixed the problem.

Rudder lines leaks can be a bit trickier. If the housing has worn out (result of constant abrasion of the stainless steel cable by operating the rudder) the water that enters the tube will leak into the hatch. Replacing the cable housing is often a pain.

10) And while I am mentioning cables I also had a few rudder cables snap on me (that’s when I still used to paddle ruddered boats). The stainless steel wire fatigues and after a while (that depends on how often you paddle) it snaps. It was no fun trying to keep that kayak go where I wanted without a rudder. While I find skegs more reliable (never kinked one myself) I have seen several malfunction. Sloppy workmanship at the factory will create sticky cables. A skeg that has resistance can kink the cable when one forgets to retract it on landing. A smoothly operating skeg will usually just retract without the paddler even noticing. I find rudders on a kayak a weak tool to keep directional stability. While without doubt they are more efficient when one’s goal is to just eat miles, I had a few snap on me when in rough waters. Don’t try reversing in surf with one deployed. I also ruined one being retracted on deck since most retention systems for stowing it on deck are not secure enough for surf work.

11)

An area of weakness and potential failure can be the carry-handle mounted to the deck. Some kayaks have simple bolt-on (in some cheap plastic kayaks it is just pop rivets) carry handles. Carry handles are not designed to pull a kayak loaded with heavy gear but some handles are secured to such thin laminates that struggle to lift the weight of the kayak alone. In one very bad case I have seen the whole handle rip out of the deck. Needless to say that reinforcing the deck so far in the bow or stern is really difficult. My preferred carry handles are positioned at the very ends of the kayak, with a line threaded through a hole at the seam of the hull/deck. More on grab handles safety issues

here

12)

Last but not least: the seat. I have cracked several seats in my kayaks. Incidentally the seats that failed were thick and heavy. So is there no seat strong enough for my paddling? Yes, there is: a decently laminated one!

I have noticed that most sea kayak seats are constructed with real cheap resin-rich chopped strand. As mentioned before this type of material is not suitable for light applications. The seats that have not failed on me are made from several layers of woven fiberglass, often reinforced in stress areas with Kevlar. Unless a weak hung seat is secured to the bottom of the hull to prevent it from swinging side to side the chopped strand will often not last too long before starting to crack in the corners. Repairing it involves removing the seat and reinforcing it with quality woven fabric. See

this article for more info.

There are a couple of other items that I have seen fail but they are accessories. I will write a separate article on those issues some other time.